This article originally appeared on Medium on 6/18/2019.

People, since the beginning of time, have been quite obsessed with the concept of self-improvement. There were bizarre Elizabethan-era beauty rituals, like using ceruse — a lethal combination of white lead and vinegar — to lighten one’s skin (this in fact, killed many of them). Being pretty wasn’t just a pastime for women in the time of Shakespeare, it was a means to social mobility and a better life for oneself, through the patriarchal Victorian marriage convention. Another historical example is the Buddha diet, noted in Buddhist literature from thousands of years ago, which health influencers now like to call intermittent fasting. People went nuts over intermittent fasting because they saw it as a way to not only get thinner, but to build mental strength and better self-control around mealtimes, improving their relationship with food over time.

Self-improvement of course, has not been limited to just maintaining aesthetic, but also to improving academic and professional skills. We’ve all seen the occasional LinkedIn post advertising something like: Do you want to accelerate the growth of your career? Are you an untalented fool? Then just join my course and I’ll fix all of that. Special promotion for the first ten people who sign up in the link below [emojis][hashtags]. Most of us know enough to turn our noses up at these sort of thing, but not everybody. People do, in fact, fall for everything from discounted public speaking course packages and new year’s weight loss resolution plans. People shell out nearly ten billion dollars a year for self-improvement products, services, and “courses”.

The self-improvement of the past was personified in things like As-Seen-On-TV body fat wraps and books by thought leaders like Stephen Covey and Wayne Dyer. It also included services; everything from personal wellness coaching, to career consulting. The new age of the self-improvement industry is going on a different trajectory, however.

Rather than products or programs, people are looking more to tools.

Why tools? At the root, it has to do with the commonly toxic and repetitive nature of self-improvement. For one, environment is exponentially stronger than willpower. Even if you’ve trained your mind to resist a particular type of cookie, the right social, olfactory, or emotional triggers can beat your internal strength very easily. This is why self-improvement products and programs generally don’t work — they push people towards an ideal, treating it as a process that can happen in some finite amount of time, and eventually leading users to failure like sheep. Rather than focus on a potentially unattainable end goal (think “I’m never going to eat a cookie again!”), tools emphasize a much more realistic option: get towards the endpoint, hopefully a little more as time progresses. It’s a lot healthier to tell yourself you’ll just try less cookie consumption.

Tools also, from a business standpoint, have infinite usability. A popular fitness plan among Instagram influencers is Kayla Itsines’ BBG (stands for Bikini Body Guide, very subtly echoing the eating-disorder-inducing rituals of her Gen X counterpart, Jillian Michaels) program. The bubbly 28-year old claims that just 28 minutes of exercise a day for three months can help women lose a lot of weight. Of course, this isn’t true. A temporary weight loss solution can’t help make the necessary lifestyle changes for a person to really turn their relationship with food and exercise around. However, a framework by which to achieve those means, like the keto diet, can have astonishingly better results. If keto, paleo, or any of their likes could be packaged up into a product, they would certainly sell; but they aren’t products by nature, which is why they work.

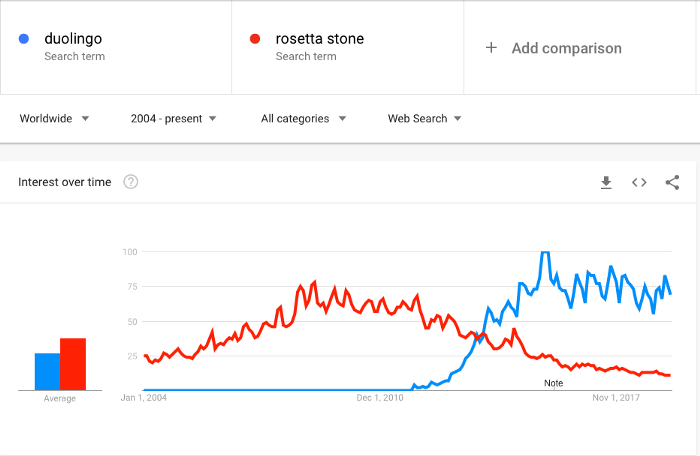

Looking at companies as a case study of the changing self-improvement industry shows similar patterns. Let’s take the market for learning languages. There’s the Rosetta Stone method, where the learning experience relies on an immersive technique where they try to simulate what it’s like to be a small child learning a language, completely immersed in it, and expected to grasp the concepts very quickly. The critical flaw is that we are not small children — we have more on our minds, and in our cognitive flow, than the task of learning a single language and that only. This is why the results promised by Rosetta Stone are often short-lived and weak. You can’t package a critical, elemental human learning process into a yellow box. Language is not a product.

In comes Duolingo — promising the same results, but taking a completely different approach. Duolingo doesn’t claim to emulate any childhood brain cycles or make you learn a language really fast, it just promises that you’ll be better at the language. You’ll know more of it at the end (if there even comes an end to your learning) than you did when you started. This less glamorous, but more realistic promise is reflected in how the courses are designed, as well. There’s no enforced immersion or cramming experience, there’s gradual, gamified spoon-feeds of new vocabulary, which makes people a lot more comfortable, anyways. And it’s free. The Duolingo Owl has been the subject of many a meme, known for its persistent reminders to get somethingdone. Not to get ten chapters done, not to force yourself into lingual panic, not to learn the language in a finite amount of time. Just to get a little better.

Language-learning methods demonstrate precisely what is wrong with self improvement products and what is so right about self improvement tools. The Rosetta Stone learning centers are losing money by the day, and seriously, when was the last time you saw one of those yellow boxes anyway? Meanwhile, Duolingo is well on its way to a near-unicorn valuation and a growing user community that only adds to its effectiveness and acclaim.

Another place where tools and frameworks have vastly outlived products is in the proactive psychology space. People want to learn how to be more productive, more liked, more successful, and more satisfied with their lives, so they like to shell out money to do so, obviously.

When I was maybe ten, my parents sent me to a day-long seminar teaching Stephen Covey’s wildly-popular 7 Habits of Highly Effective Peopleframework. I still have my copy of his youth version of the book from nearly a decade ago, and “sharpen the saw” appears in my weekly goals from time to time. Of course, I didn’t just come across this book at age ten. I had to learn the concepts again for health class in middle school, at summer programs throughout high school, and I read the e-mail newsletter religiously still, while in college. Stephen Covey didn’t just write up a book and come up with some philosophical steps towards betterment that made so much money- he created a tool, and it works. It doesn’t force any goals, timeline, or expensive products onto the 25 million people who read about it, it just provides them some insight on manageable ways they can handle their lack of aforementioned effectiveness. People are clearly not bettered by brain pills, fancy planners, or a mindfulness retreat — they are bettered by something they can rely on for the rest of their lives.

In some industries, both the product and the tool are selling themselves in a package, but one is marketed differently, so it’s seen as a lot more realistic, and then ends up outperforming its product-only counterpart. An example of this is in the beauty industry.

Curology is a digital dermatology company, creating mid-price range custom skincare solutions for users to solve their face problems. They state on their homepage, with an unnecessary amount of cheer, that “Skin is a long-term commitment — and we’re committed to you! You’ll get a full plan, designed by a provider to contain three active ingredients. As your skin changes and you keep us updated, your plan may change too!”. There’s no promise of how long it will take, no unrealistic promises, and the sale of a skincare partnership, not just some white stuff in a bottle.

OXY is a brick and mortar skincare product line, owned by a personal care conglomerate nobody’s ever heard of. It’s been around for decades, targeting the hormonally-inflamed faces of teenagers with vivid, aggressive marketing. Nearly every package advertises a time frame, or some unrealistic promise of eliminating skin care problems completely. They’re clearly selling just what’s in the bottle, while Curology is selling hope, or something more abstract like that. OXY exploits desperation, like a breakout-prone middle-schooler the night before a school dance. Curology wants to hold your hand and join you against the enemy — pimples.

The reason mere marketing sells one drying compound much better than another is because people, as a whole, have learned about the toxic cyclical nature of self-improvement. We’ve learned to see quick fixes as scams, and instead, look to more realistic, deadline-free tools that will get us a bit closer to where we want to be; this applies to pimples, language learning, and likability equally.

The company that really brings it all together is certainly Peloton. The bikes, for all practical purposes, really don’t have anything different about them (sure, they claim ergonomic benefits and better cycling experience, but if you took off the branding and muted the sweaty instructor, you probably couldn’t tell the difference) than a Precor bike. The difference is really in what shows up on the screen, which is why the Peloton is a “wellness tool,” and the Precor is an underutilized artifact in hotel fitness centers. The contrast is obvious from the start. When you hop on a Precor, it starts at some outrageous goal time, like an entire hour, to do your workout at. Besides that, your own performance, however underwhelming, is thrown at your face in big font. If you’re a bad cyclist and your shins are sore, it’s very, very obvious, and you feel bad. The Peloton interface, however, doesn’t stress the metrics or some unattainable goal; it just keeps the focus on the actual cycling. The Peloton bike is so loved because it enables fitness without forcing it. It’s a way to just get a little better, and doesn’t ever try to turn you into Lance Armstrong.

Oh, and not to mention, Peloton has nearly triple the annual revenue of Precor, despite being founded less than a decade ago.

Human beings are getting better at picking out when something is too good to be true, and this is reflected in our purchasing habits when it comes to bettering ourselves. Quick fixes don’t work, and the market has stopped paying for them.