The canonical early-stage consumer business model of the early 2010s never involved storefronts. From Casper mattresses to Glossier makeup to Allbirds sneakers, consumers had to look online to buy from the earliest, “O.G.” direct-to-consumer ventures. What all of these brands and more have in common is that they’ve launched unique, highly immersive shopping experiences at permanent physical retail locations across the US. These storefronts may initially seem counterintuitive to the way many DTC brands gain an operating edge; selling exclusively through digital channels simplifies the supply chain to a manageable network for an early-stage product, and allows for cost-reduction techniques like dropshipping.

Despite the operational burdens, consumer brands seem to be gravitating towards paying more attention to physical retail opportunities once they mature. A 2017 Casper ad, aired 3 years after its founding, touts that online-ordering, and a seamless browsing and purchasing experience were the brand’s unique value propositions at the time. In 2021, the brand can hardly be considered direct-to-consumer. You can get one of the mattresses at one of its 70+ retail locations across the country, or even at Costco, amongst household names including Sealy and Tempur-Pedic.

The US mattress market is relatively small, at only roughly $17B this year (Euromonitor), oligopolistic, and dominated by in-person sales. In other words, it’s not exactly the most nascent sector for a DTC brand to attack. Casper’s heavy physical retail expenditure seems necessary to keep up to par with the most positively-rated mattress brands in the US, the youngest of which is a company over 30 years old. Based on these characteristics of the mattress industry, Casper’s main motivation for retail expenditure is likely to attract the highest-volume category of customers for many DTC businesses — the early and late majority consumer base.

While the national market for a mattress includes you, me, and just about everyone, barriers to product discovery and purchase prevents an early-stage brand from capturing all of this potential. In a legacy vertical like mattresses, failing to sell in the same spaces as the rest of the oligopoly would be naivety.

While Casper’s motivation for physical retail operations is from a competitive product discovery perspective, other brands in highly homogenous verticals can use physical retail as a means of competitive differentiation.

Bite Beauty (now part of the Kenzo/LVMH house of brands) is a clean beauty brand sold online and in Sephora. Besides their full-face lines of products, the company offers a unique, in-store bespoke experience — the Lip Lab. Customers can come in for a consultation to have a clean lipstick custom-made, host group events, and purchase other Bite products. This custom in-store product has high potential for virality and functions more like a marketing arm rather than a major channel of distribution; not every SoHo, Vegas, or Toronto passerby is going to buy, but that isn’t even necessary in order for the physical retail to pay off overall in terms of marketing value.

Luxury brands, on the other hand, have a longstanding tradition of making physical retail experiences that are more accessible to the common consumer than the real product. You can have breakfast at Tiffany’s if you’re not in the market for high-end jewelry, or get a cup of Ralph’s Coffee around the world.

KITH is a NYC-based mid-stage apparel brand with retail experiences across the world. Many of these stores feature the KITH treats line, a cereal-inspired ice cream store with a full menu and an apparel line of its own. KITH treats pulls from the tradition of Tiffany’s and Ralph Lauren, making a little bit of the brand’s modern luxury available to anyone.

Successful examples aside, there are significant challenges for smaller brands to be able to gain from setting up physical experiences, especially when they’re digitally native to begin with. Some considerations for consumer brands evaluating building a physical experience:

Temporality: A permanent physical space, especially for an early-stage brand, is a massive fixed cost. Keeping the space stocked with inventory that may or may not sell, finding a space that will allow a short-term “pop-up” style lease, and promotions are all unexpected time and money expenditures for a brand. If adequate brand recognition and sale value can be achieved through a short-term, special-edition space, then it may be worth these costs.

Scaffolding: The retail concept doesn’t need to be fully original or independent. Collaborating with existing events or stores can be mutually beneficial. Take for example, the company Volumental. They build 3D foot scans for athletic footwear stores and more. High end running shoe brands like ON vouch for Volumental tech to be placed in stores, where their products can be suggested based on the results of a customer’s needs as determined by the scan. Another example is Mast Brothers Chocolate turning into a full-blown grocery store, selling high-end natural-category pantry staples supplied by many other manufacturers as somewhat of a “front” for their chocolate bars. The Mast example is a tried-and-true remix of how movie theaters make money.

Beyond the product: Moving from a digitally native brand identity to a physical experience introduces the difficult question of what else to include besides the actual product you’re trying to sell. What type of community members you want to attract, the types of offerings that can complement your core product, and even brand identities beyond the visual (i.e. what music and smell embodies your consumer product?) are all opportunities to make a brand very literally multidimensional.

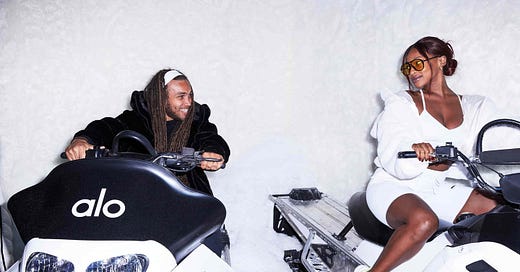

I’ll wrap up with perhaps one of the most successful recent examples of a physical experience by a (mostly) digital brand is the Alo Winter House. This was popped up by Alo Yoga, which started out making leggings and sports bras but is evolving into a full-stack modern wellness brand - they’ve come up with everything from a rejuvenating personal care line to winter jackets to college spirit wear.

This winter house wasn’t open to everyone (celebrities and influencers only), nor was anything even for sale. It’s not typically what you’d call a retail experience. But that’s besides the point; this was a fully-immersive physical embodiment of all of the glamorous health and wellness Alo brand identity. This physical experience got this identity across, even if most of us only experienced it - ironically - digitally.